Popping off, croaking, buying the farm, pushing up daisies, biting the big one, kicking the bucket, assuming room temperature, … these are some of the more colorful euphemisms for death. Not a one of them is found in the Bible.

Instead, the Bible consistently uses a metaphor for death that is viewed as neither socially or theologically appropriate among evangelicals. It calls death a sleep. But if a believer slips and refers to the dead as sleeping, judging from the reaction among traditionalists, you would think that he had shot God.

A long standing tradition within evangelical Christianity asserts that death is a move to a new level of consciousness, that those awaiting Christ’s return for reward or punishment do so in a state that looks very much like they are already being rewarded or punished. Consequently, anyone who dares to imply that the intermediate state is one of unconscious sleep runs the risk of being branded a heretic or cult member.

Nevertheless, it would do us all well to return to biblical terminology and perhaps jettison some of these traditions that keep us from using it. The biblical authors knew what they were talking about. The Holy Spirit inspired them to write words which expressed the way things really are. It is not their fault that the popular church has chosen to see and say things differently.

But in this current atmosphere where the biblical word “sleep” sparks such a response from otherwise biblically grounded saints, if conditionalists want to revive the term as a metaphor for death, they had better be prepared. Conditionalists need to know just where in the Bible the term is used for death, and what “sleep” means in the contexts of those passages.

Adam’s sleep a picture of Christ’s death

“So the LORD God caused a deep sleep

to fall upon the man, and while he slept

took one of his ribs and closed up its

place with flesh. And the rib that the

LORD God had taken from the man he

made into a woman and brought her to

the man. Then the man said, “This at

last is bone of my bones and flesh of

my flesh; she shall be called Woman,

because she was taken out of Man””

(Genesis 2:21-23 ESV).

The first place in the Bible where sleep is used as a metaphor for death apparently occurs before death existed. While in the garden paradise of Eden, Adam is anesthetized by God and surgery is performed, the result of which is Eve. Thus the Bible says that man comes from woman, and woman also comes from man.[1]

One curious thing about this incident is that it seems to have a parallel in the gospel message. Just as Eve came into existence because of the sleep of Adam, so the Church of Christ comes into existence because of his death. Because Christ slept in the tomb, his bride came into being.

If there is anything to this assumption, notice what it is telling readers about the nature of death itself. Adam’s sleep was a state of unconsciousness. He was “put under” so that he would not experience the changes taking place in his body. The purpose of this unconscious state was not to heighten his awareness, but to suppress it. One might conclude, then, that the purpose of the intermediate state is the same.

Job describes death as lying down and sleeping, not being awaken

“But a man dies and is laid low; man

breathes his last, and where is he?

As waters fail from a lake and a river

wastes away and dries up, so a man

lies down and rises not again; till the

heavens are no more he will not awake

or be roused out of his sleep. Oh that

you would hide me in Sheol, that you

would conceal me until your wrath be

past, that you would appoint me a set

time, and remember me! If a man dies,

shall he live again? All the days of my

service I would wait, till my renewal

should come” (Job 14:10-14 ESV).

In chapter 14 of Job’s story, he laments that human beings are not like trees. A tree may be cut down, but given the right conditions, it may sprout back again from the apparently dead stump. But, Job complains, human beings are not like that. When a man’s life comes to an end, he lies down and sleeps, not to wake up again.

Job is not arguing against the concept of the resurrection. Even in this chapter, he pleads with God to hide him in Sheol (death) until his wrath is past, and then remember him, causing him to live again (13-14). One cannot ask for a more clear statement of the hope of resurrection. Later, Job asserts that he has a Redeemer who lives, and that he (Job) will see God in a resurrected body, long after his present body has been consumed.[2]

So, since Job is not arguing against the notion of a resurrection, why does he insist that death is a sleep that one does not wake up from? He is contrasting the fate of humans with that of trees. Trees have something within their nature that allows them to bounce back from apparent death. God has not put such a nature within us. If we want to live again, we will need a resurrecting God. Sleep is an appropriate metaphor for death because if you see people sleeping, you expect them to wake up. Think about that the next time you walk through a cemetery. These “sleeping places” are monuments to the fact that we all depend upon God for our future life.[3]

David calls death a sleep

“How long, O LORD? Will you forget me

forever? How long will you hide your face

from me? How long must I take counsel in

my soul and have sorrow in my heart all the

day? How long shall my enemy be exalted

over me? Consider and answer me, O LORD

my God; light up my eyes, lest I sleep the

sleep of death, lest my enemy say, “I have

prevailed over him,” lest my foes rejoice

because I am shaken. But I have trusted in

your steadfast love; my heart shall rejoice in

your salvation. I will sing to the LORD,

because he has dealt bountifully with me”

( Psalm 13:1-6 ESV).

David’s lament in Psalm 13 is the complaint of a soldier who keeps losing battles, and wonders how long he can continue to hold out. The shame of the losses is coupled with the embarrassment of the taunts he hears from his enemies. They are exalted over him. They rejoice because he is shaken. Nevertheless, David is forced to trust in God’s steadfast love, and hope in his salvation. He has no one else.

David’s question to his LORD in Psalm 13 is “will you forget me forever?” If the LORD does forget his servant, he will “sleep the sleep of death” and his enemy will have prevailed over him. Death would be the ultimate failure. It would mean that God had lost a soldier, and the enemy had gained a decisive victory, and a reason to boast.

How could David have said such a thing if he believed that death was “going to his reward” or “going home to be with the LORD” or “getting promoted to heaven”? The Holy Spirit speaks of death here, not as a victory but as a defeat. Granted, it is only a temporary defeat. In Psalm 16, David predicted that the Messiah would die, but that he would not be abandoned to Sheol. He would triumph over death.

Peter, preaching at Pentecost in Acts 2, reminded his listeners of that triumph. Death is real, but Christ has overcome it. But David himself did not overcome it. He sleeps, and awaits a resurrection. In Peter’s words, “Brothers, I may say to you with confidence about the patriarch David that he both died and was buried, and his tomb is with us to this day.”[4] The old warrior did indeed sleep the sleep of death, but not before the LORD heard his cry and delivered him from his enemies.

Jeremiah speaks of Babylon’s perpetual sleep

“Babylon shall become a heap of ruins,

the haunt of jackals, a horror and a hissing,

without inhabitant. “They shall roar

together like lions; they shall growl like

lions’ cubs. While they are inflamed I will

prepare them a feast and make them

drunk, that they may become merry,

then sleep a perpetual sleep and not

wake, declares the LORD.” (Jeremiah

51:37-39).

“for a destroyer has come upon her,

upon Babylon; her warriors are taken;

their bows are broken in pieces, for

the LORD is a God of recompense; he

will surely repay. I will make drunk

her officials and her wise men, her

governors, her commanders, and her

warriors; they shall sleep a perpetual

sleep and not wake, declares the King,

whose name is the LORD of hosts”

(Jeremiah 51:56-57).

In the prophet Jeremiah’s day, the enemies of God’s people were the oppressive Babylonians. Jeremiah predicted that the great empire of Nebuchadnezzar would get drunk and fall to sleep, never to wake up again. He was prophesying the empire’s destruction,[5] in which it will fall,[6] come to an end,[7] perish,[8] and become a heap of ruins without inhabitant,[9] “a land of drought and a desert, a land in which no one dwells, and through which no son of man passes.”[10]

Jeremiah described the death of a people. It makes sense that he would use that metaphor that his ancestors did to describe that fall into a state of nothingness: sleep. It would not make sense if Jeremiah actually believed that death was a passing from one state of consciousness into another. He could have threatened an even more violent state of conscious torment in hell for God’s enemies, but he does not.

Babylon will rise no more, but someday, each individual Babylonian will stand before God and be judged for his personal sins. That day is not what Jeremiah is predicting. The end of Babylon’s judgment is death: a state of perpetual sleep. Judgment day for the individual Babylonians will come later.

In the New Testament book of Revelation, John picks up on this same imagery to describe another Babylon, doomed to destruction. He warns God’s people to come out of her …

“lest you take part in her sins, lest

you share in her plagues; for her sins

are heaped high as heaven, and God

has remembered her iniquities”

(Revelation 18:4-5 ESV).

“her plagues will come in a single day,

death and mourning and famine, and

she will be burned up with fire; for

mighty is the Lord God who has judged

her” (Revelation 18:8 ESV).

John describes the ultimate judgment day, which Babylon’s perpetual sleep only serves to predict. He is describing ultimate punishment, ultimate destruction. Jeremiah had spoken of the first death, John warns of the second.

Daniel describes resurrection from sleep in the dust

“And many of those who sleep in the dust

of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting

life, and some to shame and everlasting

contempt. And those who are wise shall shine

like the brightness of the sky above; and those

who turn many to righteousness, like the stars

forever and ever” (Daniel 12:2-3).

It is not clear what Daniel is predicting in chapter 12, but it is clear that he uses resurrection language to describe it. He speaks of those who are sleeping in the dust, awakening to everlasting life. Others who awake will not see life, but suffer shame and everlasting contempt. Jesus used the same language to describe the resurrection. He said “an hour is coming when all who are in the tombs will hear his voice and come out, those who have done good to the resurrection of life, and those who have done evil to the resurrection of judgment.”[11]

So, to both Daniel and Jesus, the anthropology and cosmology are the same: death is a sleep. The resurrection awakens all from that sleep. Judgment and eternal destiny occur at the resurrection, at the awakening. Judgment does not occur during the intermediate state, but afterward.

There are some who claim that all this talk about death as a sleep is simply Old Testament language of appearance, and that the New Testament corrects that misunderstanding by showing that the intermediate state is a conscious one. But the New Testaments speaks even more clearly than the Old in describing death as a sleep.

Jesus describes a dead girl as merely sleeping

“When they arrived at the house, Jesus

wouldn’t let anyone go in with him except

Peter, John, James, and the little girl’s

father and mother. The house was filled

with people weeping and wailing, but he

said, “Stop the weeping! She isn’t dead;

she’s only asleep.” But the crowd laughed

at him because they all knew she had died.

Then Jesus took her by the hand and said

in a loud voice, “My child, get up!” And at

that moment her life returned, and she

immediately stood up! Then Jesus told them

to give her something to eat” (Luke 8:51-55

NLT).

This story, which appears in all three synoptic Gospels, shows Jesus’ attitude toward the dead. He knows the pain that death causes, and will have opportunity to demonstrate his own grief at the death of his friend Lazarus.[12] Yet he also knows that death is only a temporary phenomenon. In that since, it is not really a death, but a mere sleep.

Make no mistake. This girl was really dead, and the scripture makes it clear that she was. Yet Jesus was there. He is the resurrection and the life. He knew that this day would not end in mourning, but a miracle. He chased all the mourners away, and woke up a little girl from her nap.

Now, if this little girl were with the angels in heaven, or even in Abraham’s bosom, and Jesus knew that, it would not have been such a nice thing for him to return her to this world of woe. But the language that Luke (and Matthew and Mark) uses matches that which the Old Testament writers had used of death. It describes this girl’s state as one of sleep, not wakefulness. Luke presented her as one who needed to be woken.

Luke’s parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus (16:19-31) contradicts the view that the Old Testament presents, and that which Jesus himself ascribes to. In that parable, Jesus speaks of the dead being conscious in the death –state, and aware of what is going on in the land of the living. Advocates of a conscious intermediate state have simply chosen to accept this view of death, instead of the one proposed in Luke 8.

Conditionalists refuse to accept the parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus as definitive teaching on the intermediate statement for several reasons, some of which can be seen in the contrast between these texts:

- Luke 8 reflects a literal event in the life of Jesus and a real human being, a small girl. Luke 16 reflects a story that Jesus told, which probably did not originate with him. He used one of the Pharisees’ stories, and ended it with a twist that they did not expect.

- The focus of Luke 8 was a real death and a real resurrection. The focus of Luke 16 was the selfishness of the Pharisees and their refusal to follow the law by having compassion on the needy. In which passage would it be more natural for Jesus to convey didactic teaching about the intermediate state?

- The witnesses of the event described in Luke 8 were Jesus himself, the young girl and his parents, and some of his disciples. The hearers of the story in Luke 16 were the Pharisees, who “were lovers of money” and “ridiculed him” because he taught that “you cannot serve God and money.”[13] In which context would it have been more appropriate for Jesus to share insight about the mystery of the intermediate state?

- The literary context of each passage is also important to consider. Luke 8 appears in a conjunction with a group of passages which emphasize who Jesus is. His authority and power are expressed in the chapters immediately preceding and following the story in chapter 8. In that context, it makes sense to show Jesus as having power to raise the dead. Luke 16 is within a group of chapters emphasizing the opposition and antagonism of those (like the Pharisees) who wanted to see Jesus done away with. In that context, what Luke wants to show is the reason why these people hated Jesus, and why his journey to Jerusalem would lead to the cross. A literal description of the intermediate state would not add to Luke’s purpose for Luke 16.

- In the final analysis, it must be admitted that these two texts do represent two alternative views of the intermediate state. In the one, people are asleep, and must be awakened by resurrection. In the other, people are awake, and are experiencing some sort of afterlife. In Luke 8, there is no reference to judgment. In Luke 16, all those who have died are already being judged.

- One cannot combine these two views of the intermediate state without distorting one into insignificance. Conditionalists accept the teaching of Luke 8 as normative, and choose to see the description in Luke 16 as representing what the Pharisees believed — not what Jesus believed — about the intermediate state.

Matthew described saints who were raised from sleep

“And behold, the curtain of the temple

was torn in two, from top to bottom. And

the earth shook, and the rocks were split.

The tombs also were opened. And many

bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep

were raised, and coming out of the tombs

after his resurrection they went into the

holy city and appeared to many” (Matthew

27:51-53 ESV).

Adding to the confusion of the events taking place on the night in which our Savior died, a number of God’s saints who had died before he did were raised to life at the moment he died. These presented themselves to the wonderment of those who had seen them die, be buried, and mourned their passing. These resurrections were demonstrations both of the power of God to raise the dead, and of the significance of the death of Christ.

Yet there are no descriptions of what these saints had experienced while being dead. They were not noted as having experienced any afterlife, but for having been raised to life again. In fact, Matthew describes them as “saints who had fallen asleep.” It was not merely their bodies who had fallen asleep, but the saints themselves. This is seen in the Greek construction of the sentence, where the word “bodies” is neuter nominative plural, and the words “the saints” and the participle translated “who had fallen asleep” are masculine genitive plural.

The anthropology/cosmology of Matthew agrees with that of Luke 8. These people had been dead, and are described as having fallen asleep. The miracle of Christ’s death on the cross caused these dead saints to revive.

Jesus says that Lazarus has fallen asleep, and the disciples misunderstand Jesus description of his death as sleep

“After saying these things, he said to

them, “Our friend Lazarus has fallen

asleep, but I go to awaken him.” The

disciples said to him, “Lord, if he has

fallen asleep, he will recover.” Now

Jesus had spoken of his death, but

they thought that he meant taking

rest in sleep. Then Jesus told them

plainly, “Lazarus has died”” (John

11:11-14 ESV).

Jesus comes face to face with the reality of death when his friend Lazarus dies as recorded in John 11. It is in this context that we read the shortest verse in the New Testament – “Jesus wept.”[14] Death is real, and it is a real tragedy. Yet Jesus describes Lazarus’ death with that same metaphor that appears throughout the text of scripture. He said that Lazarus had fallen asleep.

His disciples did not get it. They thought that he was describing the beginning of Lazarus’ recovery. They assumed that if he were (literally) sleeping, then the worst of his illness was over, and he would soon be getting better. So Jesus had to spell it out for them and explain that his friend was already dead.

Now that we can read all of John chapter 11, we understand what Jesus was doing. He was explaining to his disciples that death is not the end, because he (the Resurrection and the Life) will not allow it to be. But make no mistake about it – if there were no Jesus, death would be the end. We can call death sleep only because there is a Jesus who intends to raise the dead. Calling death sleep is a statement of faith in Christ.

Refusing to call death sleep is also a statement of faith. It reflects a faith in death itself. It joins Plato and other pagan philosophers in affirming that God created the human soul indestructible, and therefore it must remain alive after the death of the body. So the real person never sleeps but remains conscious during the intermediate state, and indeed for all eternity. Conditionalists urge our brothers and sisters to put their faith in Christ, the Resurrection and the Life.

Stephen falls asleep (dies) after being stoned

“And as they were stoning Stephen,

he called out, “Lord Jesus, receive

my spirit.” And falling to his knees

he cried out with a loud voice, “Lord,

do not hold this sin against them.”

And when he had said this, he fell

asleep” (Acts 7:59-60 ESV).

A few years ago in the Philippines, my best friend died. One of his memorial services was preached by a pastor of a denomination which teaches a conscious intermediate state. This pastor explained (using Acts 7:59) that my friend was not really dead because God had received his spirit, which flew to heaven the moment he died. The pastor explained that some people teach soul sleep, but that this text teaches against it.

Sitting in the service that day, I held my tongue. Funerals are not the place for theological debate. But later, I brought up the passage again to my students at the Bible college. I showed them that the pastor had failed to look at the context. The next verse says “And when he had said this, he fell asleep.” Luke’s description of Stephen’s death does not argue against death as sleep, but is evidence for it.

Paul teaches that most will sleep, some will be changed without it

“Behold! I tell you a mystery. We shall

not all sleep, but we shall all be changed,

in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye,

at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will

sound, and the dead will be raised

imperishable, and we shall be changed”

(1 Corinthians 15:51-52 ESV).

Paul contributes to the doctrine of the intermediate state by affirming what readers have seen elsewhere in the Bible. Death is a sleep from which believers will be awaken. This awakening will take place “at the last trumpet.” But he also teaches that there are two exceptions to the general rule that all will sleep in death:

- Some will not experience the sleep of death because they will be alive when Jesus returns. They will not sleep in death because they will be immediately changed: made immortal without ever having experienced the sleep of death. Oh, what a glorious thing it would be to be part of that group. Come, Lord Jesus!

- The other exception is Jesus himself. He slept in death, but he has already been raised from the dead. Paul calls him “the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep.”[15] He is the only one who has presently been raised immortal. His resurrection is the guarantee that we also will be raised to life some day. So, even if we miss the opportunity to be a part of that special group who will be changed into immortal beings without ever tasting death, we still have reason to celebrate. Christ’s resurrection gives us hope.

Long after the revelation of the gospel, Paul continued to speak of those who had died as having fallen asleep.[16] He was not ashamed to use that metaphor to describe what takes place at death. We should not be ashamed to do so either. To “fall asleep” or to “go to sleep”, or merely “to sleep” is an accurate, biblical statement describing the reality of death. On the other hand, to “go to heaven” or to “go home” or to “go to one’s reward” are statements which are neither biblical nor accurate.

The Christian hope is not going somewhere at death, but a Savior, who is coming to wake us up from death. That is why to “fall asleep” is a statement of faith for the believing Christian. It says that we have put our trust in a Savior who cares for us, and will not let our defeat by the enemy death be the last word.

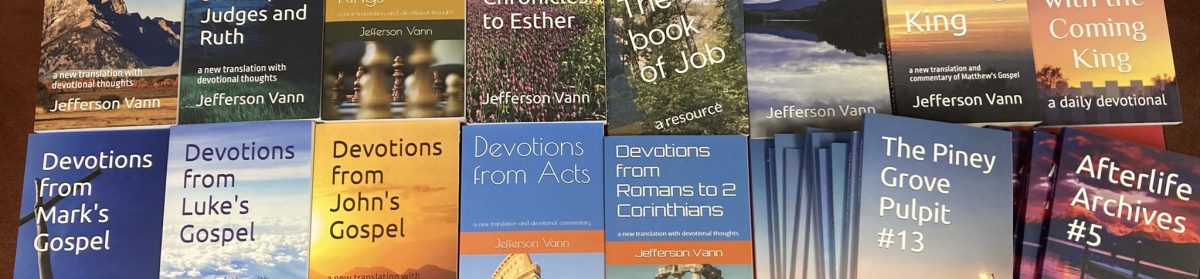

Jefferson Vann

[1] 1 Corinthians 11;8-12.

[2] Job 19:25-27.

[3] The word cemetery comes from the Greek koimhterion, which is related to the word koimhsij, used in the New Testament for both death and natural sleep.

[4] Acts 2:29 ESV.

[5] Jeremiah 51:1, 3, 20, 48, 53-54.

[6] Jeremiah 51:8.

[7] Jeremiah 51:13.

[8] Jeremiah 51:18.

[9] Jeremiah 51:37.

[10] Jeremiah 51:43 ESV.

[11] John 5:28-29.

[12] see John 11.

[13] Luke 16:13-14.

[14] John 11:35.

[15] 1 Corinthians 15:20, 23.

[16] 1 Corinthians 15:20; 1 Thessalonians 4:13, 14, 15.